by Ryna Cui

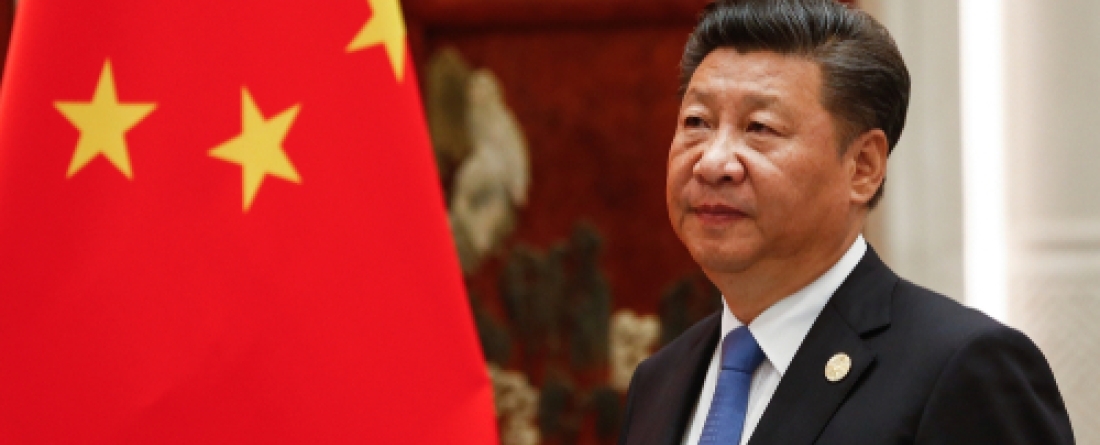

Today, President Xi Jinping made a speech at the Climate Leaders’ Summit, reiterating China’s previous goals to “peak carbon dioxide emissions before 2030 and achieve carbon neutrality before 2060.” While no new targets were expected or announced, Xi did do something new and exciting: for the first time, he called out the importance of controlling China’s coal utilization on the international stage—opening the door for further actions. Here, we summarize five key takeaways from his speech.

1) China's first commitment on coal phasedown opens up opportunities for further actions on coal

“China will strictly control coal-fired power generation projects, and strictly limit the increase in coal consumption over the 14th Five-Year Plan period and phase it down in the 15th Five-Year Plan period.”

China’s coal-dependent energy system is one of the biggest challenges to reaching its goal of carbon neutrality. China is the world’s number one coal consumer, with over half of global total coal power capacity, and appears to be poised to continue building new plants. In the domestic context, China has implemented total coal control during the 13th FYP (2016-2020); today’s statement by Xi of China’s intention to “strictly control” both total coal use and coal-fired power generation projects in the near term brings this concept to the international stage with more clarity. Most notably, President Xi also, we believe for the first time, announced internationally a timeline for the start of a “phase down” of total coal consumption after 2025. Our interpretation is both total consumption and coal power capacity will peak within the next five years at a level not far from today, and that further discussion of phasedown timelines and strategies is now possible.

These timelines are indeed necessary in order for China’s emissions to peak before 2030 and to deliver a structured phasedown toward China’s net-zero goal. However, they have been unclear and have not seemed likely to happen without additional policy direction. Coal consumption has been increasing since 2016, reaching 4.04 billion tonnes in 2020. With continued growth, coal consumption may reach or even exceed its peak of 4.24 billion tonnes in 2013. Moreover, China added 38 GW of new coal electricity generation capacity in 2020, over three-quarters of the global total, and there is 246 GW of new capacity in the pipeline, 88 GW of which is already under construction. Xi’s speech sent a clear message that the majority of these planned projects are unlikely to proceed.

Xi’s messages will force actions domestically and create room for enhanced ambition before COP26. The earlier that China starts phasing down coal, the easier it will be to complete a coal phaseout in support of its carbon neutrality goal. 18% of existing plants are low-hanging fruit: facilities that perform poorly across multiple technical, economic, and environmental criteria, and thus are suitable for a rapid shutdown while simultaneously achieving major improvements in other societal goals.

2) Peaking early in specific regions and sectors highlights subnational opportunities for enhanced climate actions

“We are now making an action plan and are already taking strong nationwide actions toward carbon peak. Support is being given to peaking pioneers from localities, sectors and companies.”

A new target for when emissions will peak has yet to be announced, yet Xi’s speech opens up opportunities for earlier peaking in specific provinces, cities, and sectors, and thus make it possible for a more ambitious peaking target for the entire country. While making sure “strong nationwide actions toward carbon peak” is underway, China can start to integrate a subnational approach into its climate action plan.

A number of pioneer provinces and cities can help demonstrate the feasibility and positive outcomes of the low-carbon transition, as well as provide insight on policy design and implementation. Lessons learned in pioneer provinces and cities can also be shared with other places to scale up changes. The emphasis on subnational opportunities also encourages leadership at provincial levels that might increase rates of implementation and create a more robust process for reducing emissions.

3) U.S.-China collaboration on climate can advance domestic actions and boost ambition internationally

“China welcomes the United States' return to the multilateral climate governance process. Not long ago, the Chinese and US sides released a Joint Statement Addressing the Climate Crisis. China looks forward to working with the international community including the United States to jointly advance global environmental governance.”

Xi expressed a strong hope for U.S.-China climate collaboration, emphasizing the recent-released Joint Statement Addressing the Climate Crisis from the two countries. Joint U.S.-China climate leadership has proven extremely influential in the past. As both countries work to increase climate ambition, this once again formal channel for dialogue and collaboration—at both the national and subnational levels—will help catalyze enhanced climate actions across countries ahead of COP26.

4) China is looking beyond domestic actions to potentially include a greener Belt and Road Initiative (BRI)

“China has also made ecological cooperation a key part of Belt and Road cooperation. A number of green action initiatives have been launched, covering wide-ranging efforts in green infrastructure, green energy, green transport and green finance, to bring enduring benefits to the people of all Belt and Road partner countries.”

China’s effect on greenhouse gas emissions (GHG) extends well beyond its borders. Through its Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), China is investing in partner countries around the world, affecting their development trajectories and their associated emissions. At the same time, China has been taking increasing leadership in areas relating to sustainable development that also overlap with climate.

However, no specific target has been determined to stop financing overseas fossil-based projects. Such a signal will be critical to demonstrate China’s strong willingness to support other developing countries in following low-emissions, sustainable growth pathways. By partnering on low-emissions and sustainable growth, China can also create new economic opportunities domestically all along the green industry supply chain.

5) Non-CO2 emissions are called out but not yet included in the overall climate goals

“China has decided to accept the Kigali Amendment to the Montreal Protocol and tighten regulations over non-carbon dioxide emissions.”

China has for many years focused its own discussion of domestic climate policies and targets primarily—-and frequently only-—on CO2 emissions. However, like most countries, while CO2 is by far the largest contributor to China’s overall GHG emissions, China also has significant sources of non-CO2 greenhouse gases that do contribute to its greenhouse impact. Most other countries focus their targets and national strategies on all gases, not just CO2 because they all contribute to the climate crisis.

China’s statements today build on the recent US-China joint statement from last week, which emphasized phasing down HFC emissions under the Kigali Amendment. And they underscore what ideally would be a continued trend toward including all GHGs in its overall national strategies and targets. It is, however, still unclear how non-CO2 emissions will be addressed in China’s overall climate pledges.

Additional measures and actions are needed in energy and land-use systems to reduce non-CO2 emissions. They include: (1) Reducing fugitive emissions from coal mining and oil and gas production; (2) Reducing F-gases in aluminum production by implementing technological and operational changes; and (3) Reducing agricultural and land-use non-CO2 emissions by increasing afforestation, controlling forest fires, improving agricultural practices, and encouraging dietary shifts.