Written as commentary by Clif Cottrell, a PhD candidate at the University of Maryland's School of Public Policy and CGS affiliate.

Last week the Trump administration released the federally mandated National Climate Assessment (NCA4), which is prepared every four years by the nation’s top climate scientists. This publication is meant to take stock of the impacts from global warming and climate change in the United States as well as prepare the country for what is to come. And the message is clear: rising temperatures will not only cost everyone extreme amounts of money and negatively impact American’s livelihoods, but will notably disproportionately affect minorities and their surrounding environments.

Between NCA4 and the also recently released 2nd State of the Carbon Cycle Report (SOCCR2), indigenous peoples of the United States are already dealing with harms from climate change, and the rapid rate at which reservation ecosystems are changing threatens traditional food practices, cultural identities, and economic development. Tribes have reported such threats as increased wildfires, diminishing wildlife, fish, and agricultural staples, and water shortages.

The unique constraints inherent to remote tribal lands exacerbate stresses brought on by the changing climate. Despite legal limitations, tribes are at the forefront of mitigation strategies and could play a key role in efforts to curb greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, preserving ways of life that have sustained for thousands of years.

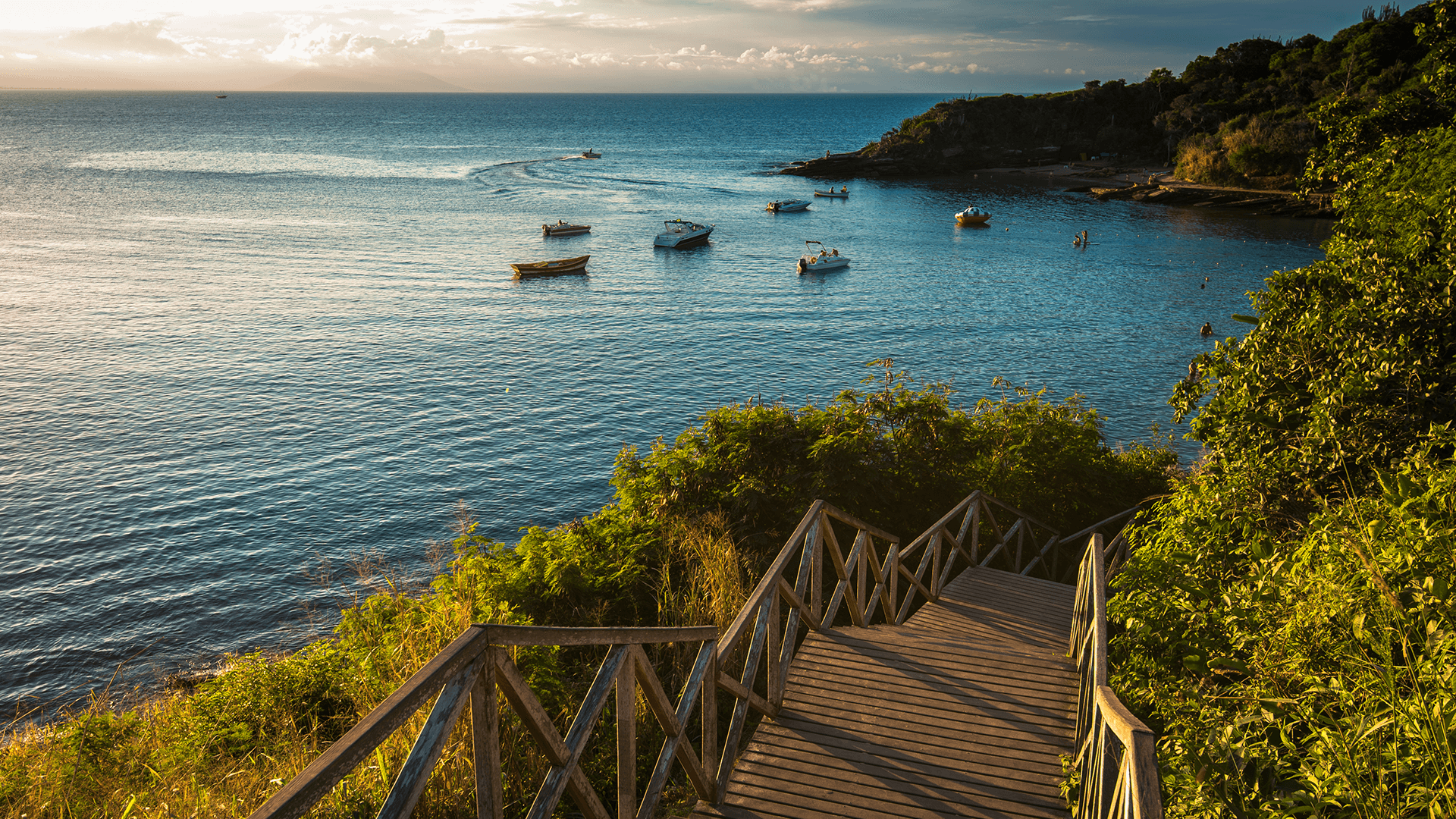

Tribal lands are crucial not only to meeting GHG emissions’ reductions, but also to ecosystem and watershed management. As noted in NCA4, “Tribal trust lands provide habitat for more than 525 species listed under the Endangered Species Act, and more than 13,000 miles of rivers and 997,000 lakes are located on federally recognized tribal lands.”

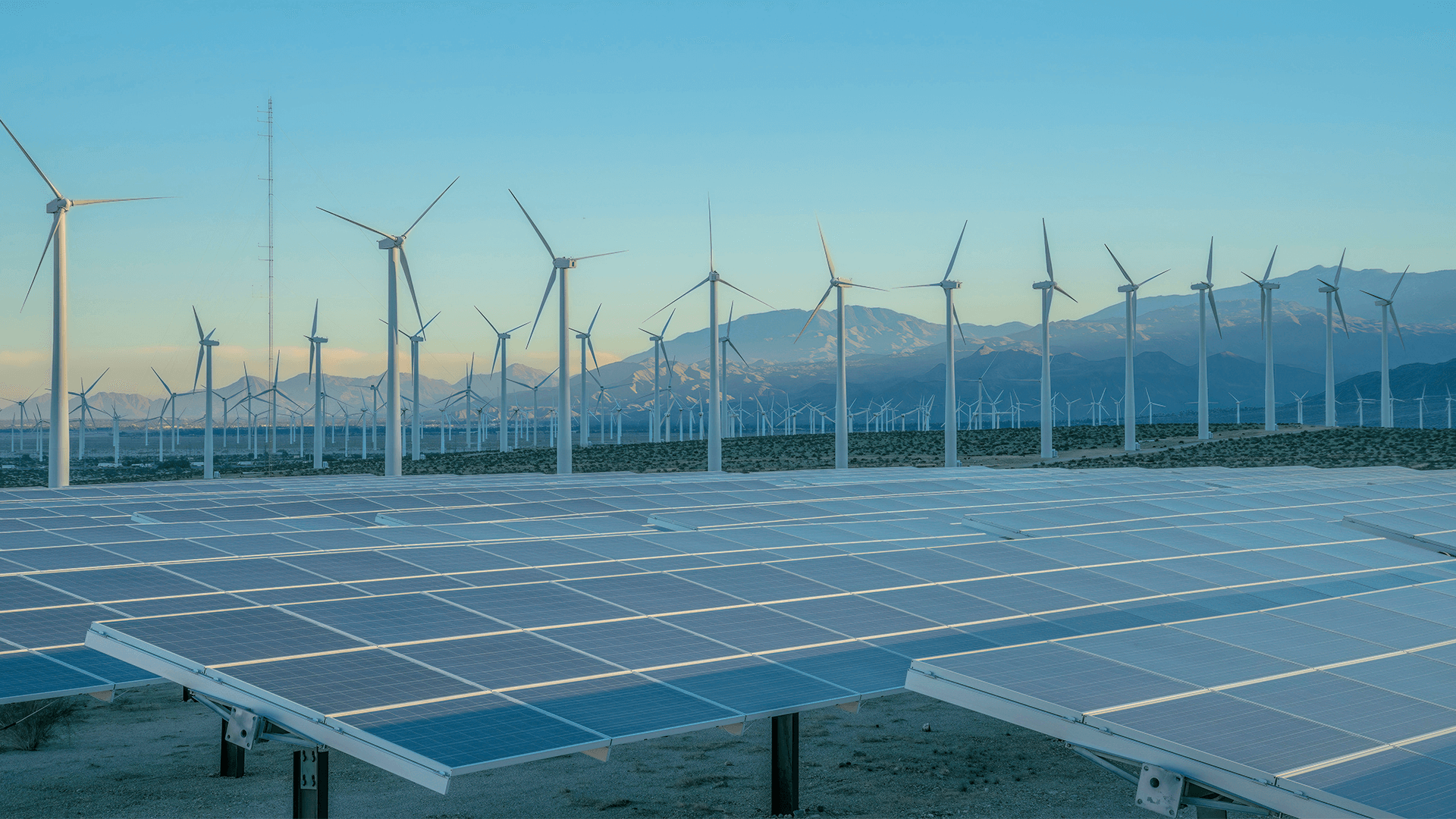

The preservation of these important resources contributes to indigenous livelihoods and culture while helping non-Native communities maintain safe access to drinking water, irrigation sources, and biodiversity. Although tribal lands comprise a mere 2% of the United States, indigenous landholdings house more than 5% of the nation’s renewable energy potential. If America hopes to meet GHG reduction targets, it will need to work with tribes to harness the abundant wind and sun on reservations.

Political, economic, and legal restraints remain a frustrating roadblock for tribes seeking to formulate adaptation strategies. Both reports highlight complicated land ownership restrictions on and around tribal lands, ineffective bureaucracy, and tribal absence from key disaster preparedness legislation as barriers to effective planning. Tribal enterprises, like commercial fisheries and agriculture, are especially vulnerable to climate threats such as sea level rise and drought. Adaptation strategies cannot overlook amending restrictive tribal land policies and key federal acts for energy efficiency, infrastructure development, and economic resilience.

NCA4 and SOCCR2 reinforce an important expansion in national environmental planning by including even more detail on indigenous groups. While the effects of climate change have not impacted all Americans evenly, some indigenous villages are already acting as a canary in the coal mine, being forced into taking extreme measures, like the relocation of entire towns, to escape harm. These reports demonstrate that effective federal policy and recognition of tribal land rights can empower tribes to build more resilient communities, while contributing to the reduction of GHGs needed to limit climate losses for all Americans.