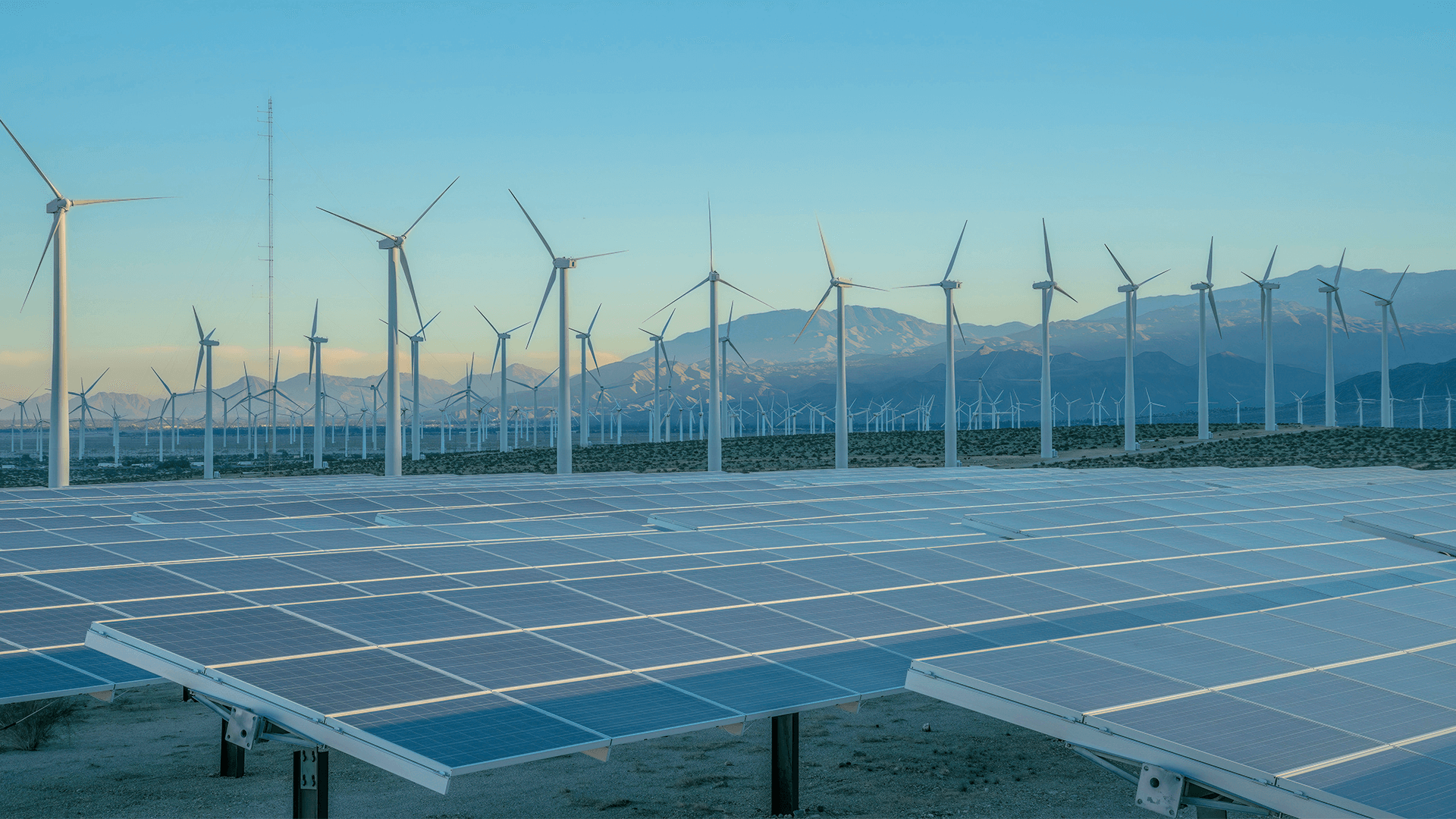

Released today, a new nine-model study in the journal Science analyzed the power plant rules finalized by the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) in May 2024. This multi-model study found that the EPA’s power plant rules could reduce U.S. power sector carbon emissions by 73% to 86% below 2005 levels by 2040, compared with 60% to 83% without the rules. The Center for Global Sustainability (CGS) joined other leading U.S. modeling teams including the Electric Power Research Institute (EPRI), Resources for the Future (RFF), the Colorado School of Mines, National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL), Andlinger Center for Energy and Environment at Princeton University, Rhodium Group, Natural Resources Defense Council (NRDC), Center for Applied Environmental Law and Policy, Energy Modeling Forum at Stanford University, and Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory to conduct this analysis.

The power plant rules establish emissions standards that allow power plant owners to choose from a range of technology and mitigation options. With this flexibility, it is critical to understand the impact of these rules. This multi-model analysis delivers critical information on not only the emissions impacts of EPA‘s power plant rules but also insights on policy design, power sector investments and retirements, policy compliance costs, and the potential implications of load growth.

“Our analysis finds that the rules can both accelerate power sector decarbonization and narrow the range of potential CO₂ emissions. In this way, they can be viewed as a buffer against higher emissions outcomes due to electricity demand growth, slower renewables deployment, and more,” study co-author Alicia Zhao, Research Manager at CGS. “The benefits extend beyond emissions reductions: These rules can also accelerate reductions of conventional air pollutants which improve public health, including in environmental justice communities that have been disproportionately affected by pollution.”

Despite these benefits, political changes and ongoing legal challenges could alter the finalized EPA power plant regulations. Other uncertainties include the pace of renewables deployment, load growth, and future policies.

Download the study here and check out the full press release below.

______________

EPA Power Plant Rules Could Reduce Emissions, Speed Up Coal Plant Retirements

What’s the story?

A new article in the journal Science finds that the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s May 2024 rules limiting emissions from power plants could reduce U.S. power sector carbon emissions by 73 to 86 percent below 2005 levels by 2040, compared with 60 to 83 percent without the rules.

The findings, which are the results of modeling conducted by EPRI, Resources for the Future (RFF), and other institutions, represent the most detailed modeling to date on this landmark policy. The nine models used by the research team not only found notable emissions reductions, but a change in power generation: coal-fired power plants retire at quicker rates under the rules while the use of natural gas, renewables, and nuclear either increases or holds steady relative to trends without the rules.

In a range of scenarios with and without the rules, the authors find that the United States falls short of the emissions reductions needed to meet its 2030 economy-wide emissions target and its 2050 net-zero goal.

How do the rules affect emissions?

Under the power plant rule, annual U.S. carbon dioxide emissions are expected to be 68 to 390 million metric tons less than under a pre-rule scenario by 2040—which is roughly the same as getting 16 to 91 million cars off the road each year. Flexibilities in the rules also mean that the costs of emissions reductions can vary from $6 to $44 per ton of carbon dioxide.

Aside from reducing carbon dioxide emissions, the rules could reduce conventional air pollutants. This is largely due to the decline in coal-fired power plants in operation. The models show an 88 to 98 percent reduction in sulfur dioxide by 2035 compared to 2015; under pre-rule policies, this estimate is 70 to 88 percent. Nitrogen oxide emissions could fall by an estimated 84 to 94 percent under the rules, compared to 74 to 90 percent under pre-rule policies.

Sulfur dioxide and nitrogen oxide damage human health and are particularly burdensome to low-income communities and communities of color. These projected pollution reductions could bring with them air quality benefits that improve public health.

What about power sources?

The new power plant rules establish emissions standards rather than technology mandates. This means that power plants can choose from a range of technologies and emissions control options to meet the standards.

The new modeling finds that the rule could accelerate coal plant retirements. It projects fewer coal plants in operation by 2040 than EPA’s own modeling. Instead of adopting carbon capture and sequestration technologies permitted under the rules, many coal plants would likely opt for lower-cost pathways such as faster retirements, contributing to reductions in sulfur dioxide and nitrogen oxide.

These coal-fired power plants are likely to be replaced by natural gas-fired power plants, energy storage, renewable energy sources, and existing nuclear power plants.

How do these rules interact with legislation like the Inflation Reduction Act?

Power sector emissions were already expected to fall over the next few decades due to legislation like the Inflation Reduction Act, falling costs of renewables, and other trends. Without the rules, power-sector emissions are expected to decrease by 60 to 83 percent from 2005 levels. With the rules, power sector emissions are expected to fall 73 to 86 percent—meaning that the rules could be associated with steeper reductions and a narrower uncertainty range.

What’s next?

While the technologies needed to meet growing electricity needs exist today, the United States’ future power generation mix remains unclear. Although the modeling accounted for growing electricity demand spurred by electrification and growing demand from data centers, energy demand and prices may change over the next few decades. Technology costs, too, may vary. The future of the rules themselves may also be uncertain, as they may be revised or challenged under the new administration and by lawsuits. These uncertainties lend urgency to the overarching goal of this paper: to provide timely analysis that may help decision-makers understand the effects of existing and potential regulations.

Where can I learn more?

Read the article, Impacts of EPA’s Finalized Power Plant Greenhouse Gas Standards, in the journal Science.

The authors are John Bistline (EPRI), Aaron Bergman (RFF), Geoffrey Blanford (EPRI), Maxwell Brown (Colorado School of Mines), Dallas Burtraw (RFF), Maya Domeshek (RFF), Allen Fawcett (University of Maryland, College Park), Anne Hamilton (National Renewable Energy Laboratory), Gokul Iyer (University of Maryland, College Park), Jesse Jenkins (Princeton University), Ben King (Rhodium Group), Hannah Kolus (Rhodium Group), Amanda Levin (Natural Resources Defense Council), Qian Luo (Princeton University), Kevin Rennert (RFF), Molly Robertson (RFF), Nicholas Roy (RFF), Ethan Russell (RFF), Daniel Shawhan (RFF), Daniel Steinberg (National Renewable Energy Laboratory) Anna van Brummen (Rhodium Group), Grace Van Horn (Center for Applied Environmental Law and Policy), Aranya Venkatesh (EPRI), John Weyant (Stanford University), Ryan Wider (Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory), and Alicia Zhao (Center for Global Sustainability).