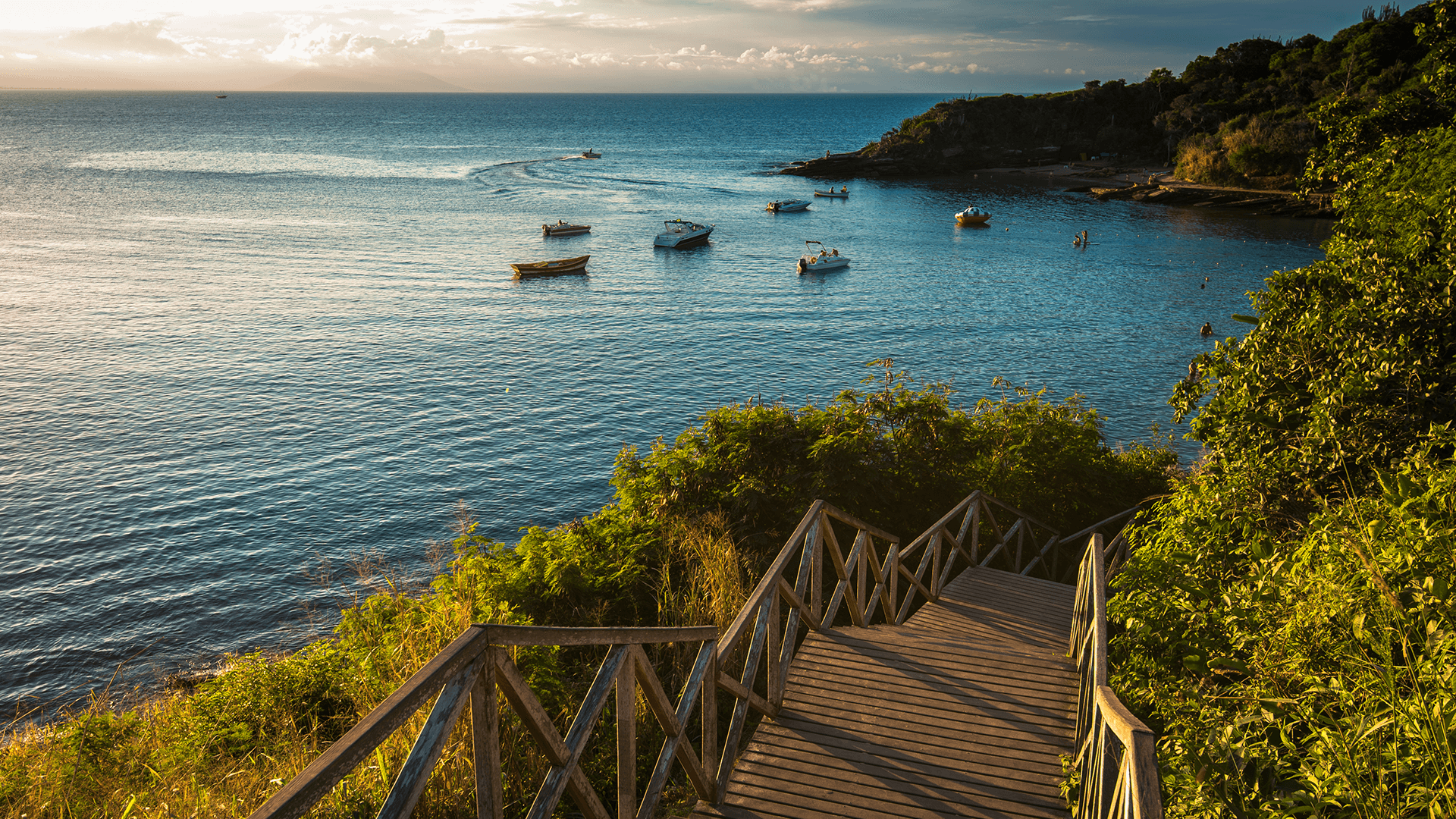

Nautical nightmare: How boat regulations pose challenges to U.S. offshore wind development

By Paige Hawksworth, Research Assistant, Center for Global Sustainability

Offshore wind energy offers increasing potential to reduce substantial emissions in the United States and help support national and state-level climate goals. Despite the significant generation potential of offshore wind, a little-known, 100-year-old legal obstacle hinders the adoption and development of this underexplored renewable energy source. The Merchant Marine Act of 1920, also called the Jones Act, dictates that only "U.S.-built-and-operated" ships can transport goods between U.S. ports—making shipping of materials from Europe hard to move between ports during the installation of the turbines.

With the ambitious goal of 30 GW of installed offshore wind capacity by 2030, the U.S. has the opportunity to develop a thriving offshore wind market within the next decade. The California Energy Commission voted to adopt state-wide offshore wind energy preliminary planning goals this month. While the goals vary in range, they are higher than the initial proposed goal for 2045 as part of the state’s broader push to decarbonize its electric grid. This vote comes in response to California Governor Gavin Newson signing an agreement to open up the state’s coastline for offshore development last year. As more projects start in the coming years, Californian offshore wind developers, like others in the U.S., will encounter the Jones Act—complicating offshore installations.

Offshore wind power takes its energy from the force of winds at sea and transforms it into electricity to supply networks onshore. Since these offshore facilities are taking advantage of wind power, the conversion into energy creates no harmful greenhouse gas emissions, making it a renewable energy source. Compared to other renewable sources, offshore wind can occur 24 hours a day, whereas other renewables, such as solar, can be hindered by intermittency. Wind turbines sited far out at sea also minimize challenges associated with onshore siting and development. The National Renewable Energy Laboratory estimates that the technical resource potential of US offshore wind is more than 4,200 GW.

Yet the Jones Act threatens offshore wind development and the U.S. achieving potential emissions reductions. Delayed permitting processes and Jones Act requirements are often cited as why the U.S. is falling behind in the global production of offshore wind. These restrictions include: limiting cargo transfers between U.S. ports to vessels registered; vessels must be owned by a majority of U.S. incorporated entities with U.S. citizen representation; onboard vessel crews may use only United States Coast Guard (USCG) credentialed mariners and a majority of U.S. citizens.

More recently, the Jones Act impacted the Block Island Wind Farm off the coast of Rhode Island. With a lack of U.S. vessels, developers contracted a vessel from Europe, but the Jones Act meant the ship was prohibited from entering U.S. shores to collect and transport wind turbines, towers, and blades. To overcome this issue, smaller U.S.-flagged liftboats were used to deliver wind turbine equipment out to the site, where they were transferred to the European jack-up vessel, which inevitably increased the cost, complexity, and carbon footprint of the project.

While the Jones Act presents challenges for development, the vast potential for offshore wind has increasingly spurred investment into offshore facilities as viable alternatives for renewable energy generation. Overcoming these logistical and regulatory issues will require policies streamlining the permitting process and addressing trade barriers. State policy and leadership also have the potential to be effective in offshore wind development by garnering community support and determining offshore installation goals and incentives to increase demand for offshore investment from developers.